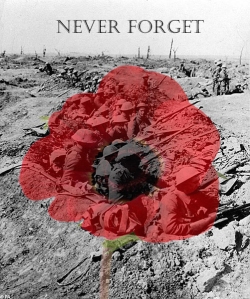

God speed this bullet

96 years ago the First World War, the Great War, was finally over. A generation of young men, those that returned home, were left to pick up the pieces of what they had experienced, seen and endured. They said it could never happen again. but it did; 21 years later. As terrible as the Second World War, the same as any war, was, there is something truly horrific about the trenches.

***

The ground heaves and shakes and small rivers of dirt fall, splattering my helmet and the pounding of the earth is like a fist in my back. I look at Jenkins; he’s now bleeding from the ears and nose from the concussion of this incessant artillery barrage. I look at the lieutenant; his face flares white in the explosion flashes; dark rings his eyes and he’s gaunt, like the rest of us. He’s one of us now. After two years in this hell-hole the only part of Cambridge that remains is his manners. He looks at me.

‘Don’t,” he says.

He knows I want to look, I can’t help it; George was my friend from the pre-war days. George who had the nerve to stick his head above the trench, only for a piece of shrapnel to tear it off and fling the rest of him across the trench. The trench, this devil-made wormhole. What will I tell his wife when I get back…if I get back?

A let up in the barrage and the shadow of the black Somme night passes across the trenches, leaving destruction, torn and twisted bodies, fatherless children and husbandless wives but now all was silent. We’ve been stuck here for months, barely advancing, barely retreating. The smell of the ripped earth and dank mud in which we wallow is everywhere, except when the wind blows towards us and the stench of death and decay replaces it.

‘Help…’

The voice is faint but it’s there. In the sudden and welcome silence it’s as clear as birdsong on a June morning, agony and suffering coming through in just one word.

‘Who the bloody hell is that?’ Symes; newly arrived from the train, all shiny boots, clean puttees and enthusiasm. They always arrive with enthusiasm. What the hell are they telling them back home? Five days a week killing the Hun then Saturdays and Sundays off, French whores and bistros thrown in? ‘Can we not do something for that poor bugger sir?’ he says, turning to the lieutenant, who sighs.

‘Corporal, take a look and be bloody careful.’

I take off my helmet and place it on the butt of my rifle and slowly raise it above the trench, joggling the rifle to simulate movement: nothing. No sniper fire to split the night. The lieutenant hands me his field-glasses as I replace my helmet and climb the ladder. They say there’s nothing blacker than no-man’s land at night but that’s not strictly true, especially following a barrage. The artillery will always find something to burn, even if it’s just human remains, and little fires dotted around cast an unholy light in the field-glasses. I first scan the enemy lines, looking for movement, but I see none.

‘Help…’

My vision jumps from crater to crater, searching for life and hoping for it also, in this God-forsaken pit of human misery. At first I see nothing, then I take a slower, longer sweep with the glasses. I see movement; slow, shambling movement some twenty yards away where the barbed-wire is stretched across and upon which hang torn and crow-picked corpses, like some infernal spider’s web. A slow, crawling movement catches my eye and even in the dead-light I can see enough. It’s a soldier, a German soldier, gone from the waist down, pulling and dragging himself inch by agonised inch towards our trench.

‘Well I’ll be damned. It’s a Jerry sir and in an awful state by the looks of it.’

‘What the Dickens…’ as he climbs up, taking the field-glasses from me and looks upon the awful site before us. He wipes his mouth with the heel of his hand, sighed and turns, stepping down into the trench. Not a moment too soon, as a high whistling noise is followed by chaos. The concussion from the blast is enormous, filling my head with a death-roar and I could feel my ears and nose bleeding freely. Symes is on the floor of the trench, his legs pinned down by dislodged sandbags but he’s ok. Upon hearing that whistle, the lieutenant, Jenkins and I all threw ourselves against the wall of the trench. Symes will learn, if he has time.

‘Corporal, who’s our best shot?’ but he looks at Jenkins, the Welshman is a crack shot and needs no introduction.

‘Help…’

‘Take him out Private. I won’t risk stretch-bearers to bring him in but the sorry blighter has suffered more than enough.’ He moves aside from the ladder to let the Private through. The figure is nearer now but still a good fifteen yards away. No trouble for Jenkins, who could shoot a canary in a Welsh coalmine from fifty. The first signs of dawn are beginning to pink the early clouds, which a rising breeze is scattering. Jenkins brings the rifle up to his right shoulder, intent only on what he sees at the end of the barrel.

“God speed this bullet and put that poor devil out of his misery”, the lieutenant says, to no one in particular.

“Amen,” says Jenkins, and his finger tightens on the trigger.

As if in response the morning sun throws its first rays of light through the breaking clouds and onto the battlefield. The bombardment has done a lot but not enough; the barbed wire is still in place. If we have to go over the top we’ll be torn to pieces by the German machine-gunners.

The report of Jenkins’ Lee Enfield barks out. The lieutenant raises the field-glasses but they aren’t needed. As more lights floods across the battlefield the sliding, shuffling figure shimmers and fades to nothing.

We look at each other in silence. We’ve all heard stories of ghosts on the battlefield and I guess with so many men butchered on a daily basis it was only a matter of time. I wonder, should God grant any lasting peace on this Earth, in 100 years how many of our souls will still wander here, lost in a foreign land far from home.

***

I’d like to acknowledge http://femaleimagination.wordpress.com/2014/11/11/11-november-world-war-i-ends/ for the use of the photograph.